The Lines We Learned to Live Inside

Borders, Nationalism, and the Search for Belonging

What if the very movement we now treat as a crisis was once the heartbeat of human survival?

For most of human history, movement was not a problem to be solved. It was how life worked. Humans followed water, seasons, animals, soil, and one another. Migration was not an exceptional event but a recurring rhythm—an adaptive response to climate, scarcity, conflict, and opportunity. Cultures formed not by staying put forever, but by knowing when and how to move.

The world we inhabit now—divided by hardened borders, moralized crossings, and national identities tied tightly to territory—is not the human norm. It is a relatively recent arrangement. And it is increasingly strained by conditions it was never designed to hold.

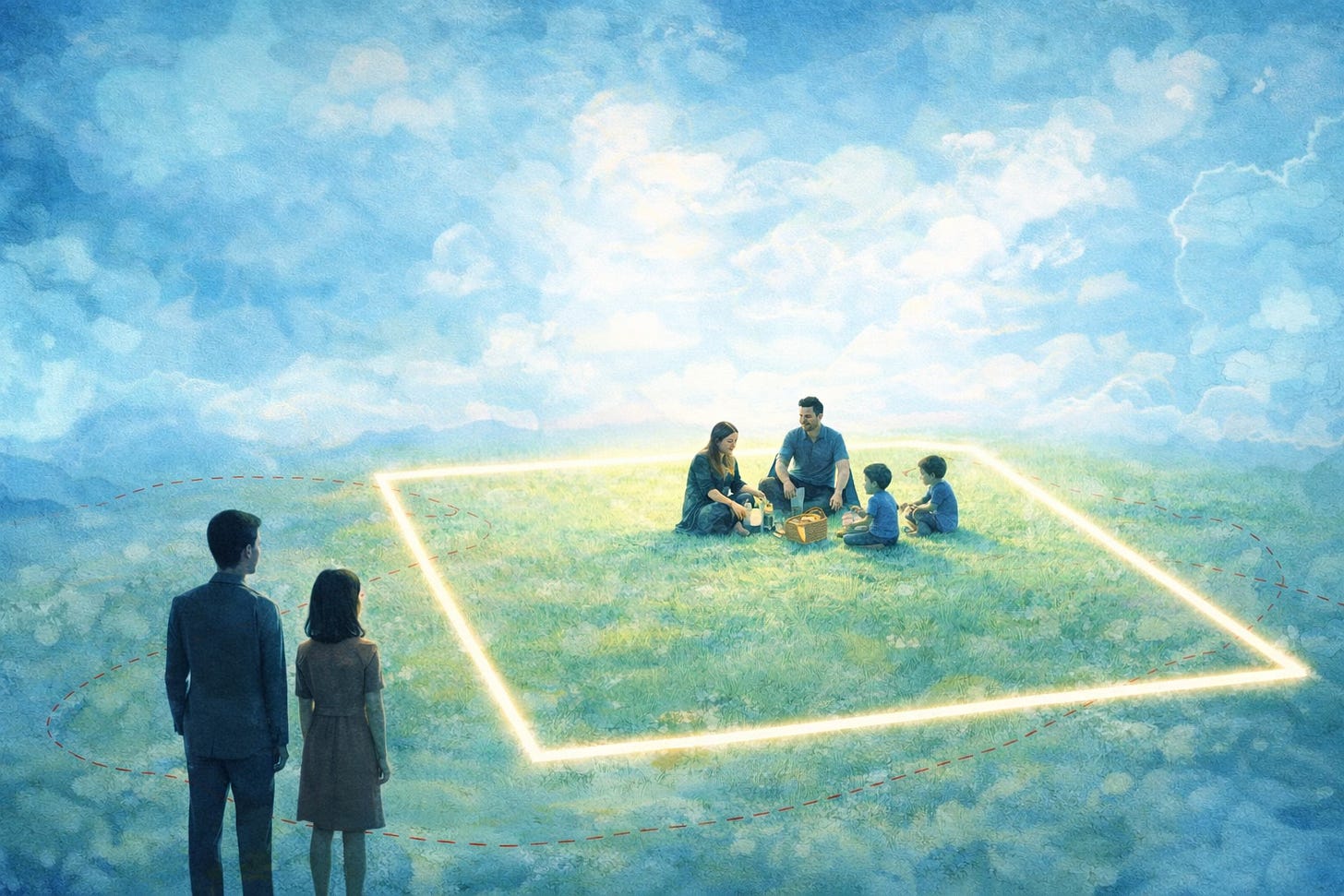

To understand why borders feel so emotionally charged today—why they provoke fear, loyalty, and moral certainty—we have to look beyond policy debates and into the deeper question of belonging. Not just where lines were drawn. But what those lines came to mean.

From Relational Belonging to Territorial Identity

In deep time, human societies did not organize belonging through fixed, exclusive territory. Land was used, shared, revered, crossed. Boundaries existed, but they were relational—seasonal ranges, kin networks, sacred sites, zones of exchange. Belonging emerged from participation: shared responsibility, reciprocal care, and ongoing relationship with place and people.

And that participation was maintained through practice, not declaration.

Belonging was renewed seasonally. Harvest ceremonies redistributed resources and reaffirmed relationships. Winter gatherings transmitted knowledge through storytelling—which plants healed, where water could be found in drought, how ancestors had survived disruption. Spring plantings synchronized labor and mutual aid. Solstice ceremonies marked the year’s turning and realigned community with cosmic rhythm.

These weren’t quaint traditions. They were the technologies through which belonging was sustained. You didn’t belong because of where you were born. You belonged because you participated in the cycle—because you learned when to plant and when to let rest, how to read the land’s changing signals, when abundance should be shared and scarcity endured together.

This knowledge couldn’t be transmitted through documents or abstraction. It required doing, seasonally, year after year. Children learned by participating. Elders held memory across generations. The community’s relationship to place was embodied knowledge, renewed with each repetition of the seasonal round.

Even early civilizations and empires did not rely on borders as we understand them today. Authority was layered and overlapping. Frontiers were porous zones of interaction rather than hard lines of exclusion. People moved across them constantly: traders, pilgrims, laborers, refugees. Identity was plural. Allegiance was contextual. Belonging was practiced, not inherited.

What changed was not simply where power resided, but how belonging was imagined.

Borders as Moral Containers

With the rise of the modern state, sovereignty became territorial, exclusive, and supreme. Borders hardened. Populations were made legible. Movement became regulated. But borders did not become powerful because they were efficient administrative tools alone.

They became powerful because they absorbed moral meaning.

As older forms of belonging—rooted in land, lineage, shared obligation, and long memory—were weakened by industrialization and abstraction, the nation emerged as a substitute container for identity and care.

What was lost was not just land, but the practices that had maintained belonging to it.

Forced sedentarization, industrial time schedules, religious conversion, compulsory education—these did not merely relocate people or change their beliefs. They severed the calendrical practices that had synchronized human life with ecological and cosmological rhythms. Harvest festivals were replaced with market days. Ceremonial calendars gave way to factory shifts. Seasonal variation was eliminated in favor of year-round production.

When you can no longer read the land’s signals because you’ve been moved off it, when you can no longer mark the year’s turning because your time belongs to wage labor, when the stories that carried memory are deemed backward or pagan, belonging becomes something that must be claimed rather than practiced.

Loyalty to territory replaced relationship to place. Citizenship stood in for belonging. Borders became not only administrative lines, but moral membranes: inside was order, legitimacy, and protection; outside was disorder, threat, and excess.

Nationalism did not arise because people suddenly loved borders. It arose because something else had been lost.

Why Nationalism Feels Necessary

Nationalism offers a promise that is deeply human: continuity, meaning, and protection in an uncertain world. It answers the question Where do I belong? with a simple, inherited story—one that does not require daily practice or relational responsibility.

This is both its power and its fragility.

The older forms of belonging required ongoing participation. You had to show up for the harvest. You had to share what you gathered. You had to learn the stories and pass them on. You had to mark the seasons and adjust your activity to their rhythms. Belonging was not automatic. It was maintained through reciprocal care, year after year.

Nationalism offered something easier: belonging through birth. Through paperwork. Through symbols you could salute without having to practice anything at all.

In times of relative stability, this substitution can hold. Abstraction can stand in for relationship. Symbol can stand in for care. The nation can feel like a home.

But this arrangement is fragile. It depends on stillness: stable climates, predictable economies, manageable movement. When those conditions unravel, the emotional load placed on borders becomes unbearable.

Climate Migration as the Stress Test

As planetary conditions destabilize, movement is returning—not as preference, but as necessity. When land no longer grows food, when water disappears, when heat becomes lethal, people move. This is not moral failure. It is adaptation.

Borders were built to regulate optional movement in a relatively stable world. They were never designed to govern planetary instability. As climate disruption accelerates migration, borders are being asked to carry moral meaning they cannot sustain.

The result is not order, but panic. Not coherence, but escalation. Movement, once understood as adaptive, is reframed as threat. The moral membrane tightens precisely where it is weakest.

The Deeper Question Beneath the Border

The question before us is not whether borders will disappear. They will not, at least not soon. The deeper question is this: What do people hope borders will give them—and where else might that be found?

Belonging is not the same as citizenship. Citizenship is legal recognition by a state. Belonging is being held in a web of care, responsibility, and meaning.

For most of human history, belonging was cultivated through:

Place without ownership — knowing a landscape intimately through seasonal return, not permanent possession

Practice rather than identity — participating in the rhythms that sustained life, not simply claiming a heritage

Calendrical continuity — marking solstices, moon phases, harvest times; understanding time as cyclical rather than linear

Shared responsibility over time — obligations renewed seasonally, reciprocity practiced across generations

These forms of belonging did not require sameness. They did not depend on exclusion. They were relational, adaptive, and capable of moving as conditions changed.

They were also materially different from what nationalism offers. They required attention. They required presence. They required learning to read the world’s rhythms and adjust your life accordingly. You couldn’t belong by assertion alone. You had to practice it.

The Quiet Work Ahead

In a time of accelerating movement, the future will not be held together by lines alone. It will be held—if at all—by practices that restore orientation: to land, to time, to relationship, to consequence.

This means recovering what was severed when belonging became abstraction: the capacity to know a place seasonally, to let your activity shift with the year’s rhythm, to understand yourself as part of rather than owner of the land you inhabit.

It means relearning what older societies knew: that reciprocity with place creates rootedness without rigidity. That ceremonial marking of the year’s turning synchronizes community and renews care. That knowledge transmitted through practice, not doctrine, creates continuity without requiring conformity.

This is not nostalgia for a world that can’t return. It is the recognition that the practices which once made belonging possible without borders are precisely what we need now—not to eliminate borders, but to stop asking them to do work they cannot do.

This is not a call to abandon discernment or responsibility. It is a call to recognize that borders have been asked to do the work of belonging—and they cannot.

The human story did not begin with borders. And it will not end with them.

The work now is not to stop movement, but to relearn how to belong in a world shaped by change.

That relearning is not theoretical. It is practical, seasonal, embodied. It begins with simple questions: What is ready now? What needs rest? How do I mark this turning? Who shares this place with me, and what do I owe?

It begins with practice—and practice, renewed over time, is how belonging was always made.